DON’T PANIC

The Clinician’s Guide to the Genomic Galaxy is designed to help you navigate the genomic landscape that is materializing beneath your feet as we speak. It is materializing quickly; we should learn to walk now so that we may run in the days ahead.

When clinicians first encounter next-generation sequencing (NGS), or hear it discussed at conferences, the road is difficult to see through all the caution signs and while caution is certainly appropriate, these signs are often treated like “road closed” signs. Some of the cautionary statements that frequent discussions of molecular diagnostics are:

- NGS is too expensive.

- NGS is too slow for clinical use.

- NGS will identify all DNA in the sample whether or not it is viable.

- NGS has poor specificity, or too many false positives.

Some of these are currently true and some of them used to be. Of the statements which are no longer true at the time of writing The Clinician’s Guide to the Genomic Galaxy, NGS is no longer “too slow” or “too expensive”. Many widely used diagnostic technologies are now more expensive and/or slower than NGS which can be done for under $500 in less than 48 hours. To put that in perspective, the current test method used overwhelmingly in hospital laboratories is culture and sensitivity (C&S). C&S must be run separately for aerobes, anaerobes, mycobacteria, and fungi. Additional PCR testing is typically required for viruses and parasite identification, though they may not always be necessary. A culture set just covering bacteria and fungi can cost over $900 and take as long as 28 days to be ruled negative.[1] AFB cultures can take as long as 6 weeks for positive identifications. And no matter what kind of cultures are being run, only about 2% of the bacteria we are aware of can be grown in routine cultures, so there is a big diagnostic blind spot.2-4 Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of cultured isolates adds cost, time, and only shows the planktonic susceptibility in vitro and may not be reflective of the biofilm’s susceptibility in vivo where tolerance alone can exceed MIC by 1000X. Molecular approaches including NGS can detect bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites typically within 48 hours for less cost than a comprehensive culture set.

Regarding the ability to detect viable and non-viable nucleic acids from patient samples, NGS can absolutely “see” them both. That is why any molecular lab that knows what they are doing is going to use some clever thresholds that can help mitigate the reporting of known reagent contamination as well as low-abundance non-viable DNA and sample collection contaminants. Different labs and workflows will use different thresholds, but typically a certain number of sequenced reads are required to call a sample positive and then a second threshold to determine whether or not to call a certain organism positive. At MicroGenDX, for a sample to be called positive, there must be at least 1,000 sequenced reads from that sample and for an organism to be listed on the report it must represent 2% or more of the sequenced reads. These thresholds keep contaminants and non-viable DNA off the report in most cases. In low biomass samples, like synovial fluid or CSF, DNA from non-viable cells or sample collection contaminants is not always caught by the thresholds, but reagent contamination is controlled for by a “no template” control which allows for bioinformatic removal of those sequences.

When the thresholds do not prevent sample collection contaminants or cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from the nonviable organisms from making it onto the report, these are considered false positives even though they are present in the sample. Let’s take a moment to think about false positives and specificity.

When tests have low specificity, that means they produce a lot of false positives. That has certainly been said about NGS, but why?

A review of the literature on tests of diagnostic accuracy that compare culture to NGS will show you that there is no significant difference between the methods, so NGS isn’t any more likely to produce a false positive result than C&S.5-7 The idea persists because NGS is usually positive while cultures are often falsely negative.

We really need to quit calling culture the “gold standard.”

In some cases, those “false positives” that NGS is spitting out are clinically informative. Consider a vaginal swab from a patient with suspected bacterial vaginosis. In our experience with the terminology surrounding NGS, a finding of Lactobacillus would be considered a false positive because that organism isn’t causing infection. It should be argued that this is not a false positive result at all as it accurately reflects the molecular signature identified in the specimen. If Lactobacillus is not the dominant organism on a vaginal swab, that pattern supports concern for dysbiosis, with the dominant organism likely responsible. In contrast, when Lactobacillus is the dominant or sole organism detected, the symptoms are unlikely to reflect a vaginal bacterial or fungal problem and may instead arise from another source.

Although NGS reports often include low-level detections of normal skin flora in biopsy tissue, surgical specimens, CSF, or other low-biomass samples, these findings should not be viewed as a weakness of the technology. They simply reflect the molecular reality of the specimen and the unavoidable imperfections of collection, especially in procedures where even excellent sterile technique cannot eliminate trace background DNA. The presence of these organisms does not make them pathogenic; it highlights the need for interpretation grounded in anatomical expectations and pretest probability.

In fact, NGS turns what culture would have dismissed as “mixed flora” into actionable, organism-level data that is particularly valuable in orthopedic and biofilm-associated infections where polymicrobial communities are common and clinically important. Rather than troubling the clinician, these signals should prompt a thoughtful history and physical exam to determine whether the findings represent a complex biofilm infection, as in the urine example discussed later, or simply the consequence of collection technique. In many ways, this granularity is a boon: it allows the clinician to work with real data, rather than culture-based ambiguity, to understand the true microbial landscape of the specimen.

While it might be safe to consider these concerns as having been addressed, the concern of how to determine which organisms require medical intervention and which do not, remains. I wish I could I say, “Pretend this a culture report, what would you treat?” We need a little more than that to address the concern.

Now, our task is to move beyond detection and into interpretation. To learn when to act, when to wait, and when the smartest move is restraint.

The remainder of The Clinician’s Guide to the Genomic Galaxy is devoted to case vignettes and is designed to provide clinicians with some practical tips for determining when to pull out that prescription pad and when to recommend rest and fluids.

BLOOD

Blood is a bit of a troublemaker in molecular diagnostics. It’s loaded with inhibitors that make DNA extraction and amplification more of an art than a science. Even when we do detect pathogen DNA in blood, we’re left guessing where it came from, unless the patient has bacteremia or fungemia, that clue leads nowhere. For cases without a clear source, like fever of unknown origin, blood testing can help narrow the field. But whenever you have a likely infection site, go straight to the source. The closer you are to the action, the clearer the data.

Blood Case 1:

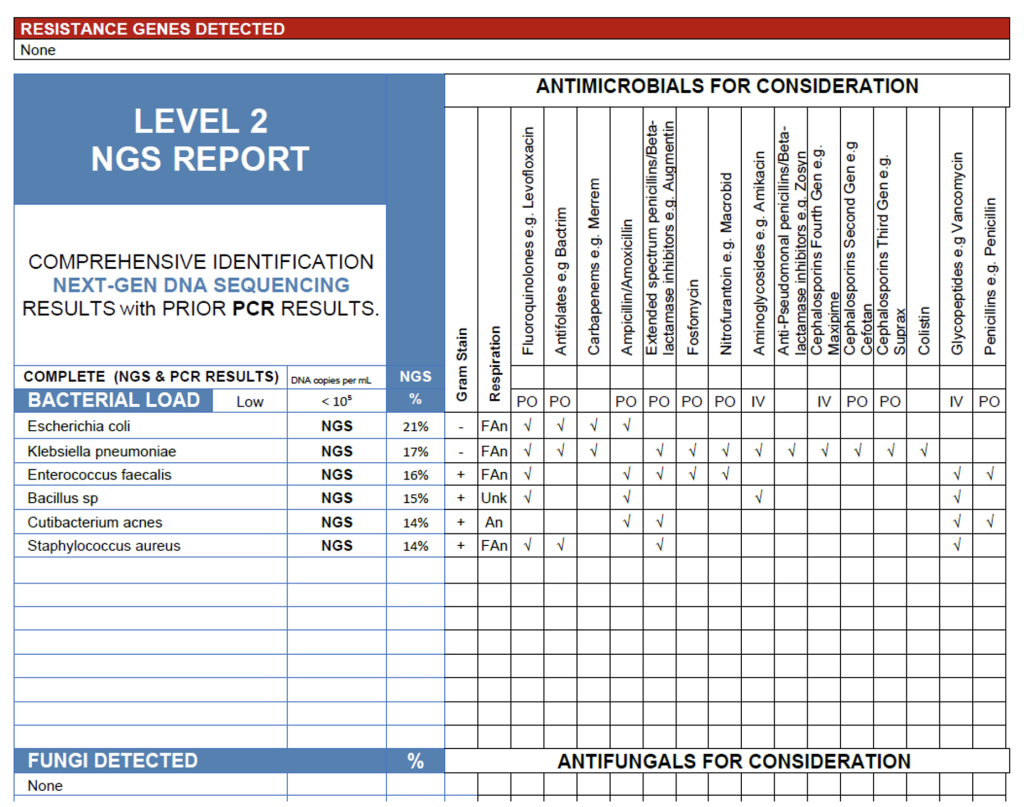

The NGS profile from this blood sample reveals a low overall bacterial load (<105 copies/mL) with a mixed signal dominated by Escherichia coli (21%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (17%), and Entercoccus faecalis (16%), organisms commonly associated with bloodstream infections of genitourinary or gastrointestinal origin. In a symptomatic patient, these taxa are the most likely contributors to active infection, reflecting a possible polymicrobial bacteremia or translocation event from the gut or urinary tract.

Minor contributors include Bacillus spp. and Cutibacterium acnes, which are frequent environmental or skin contaminants and may reflect background DNA introduced during sample collection. However, the detection of Staphylococcus aureus (14%) warrants additional consideration due to its known pathogenicity and potential to seed bloodstream infections, even when present at low relative abundance. Clinical correlation is advised, particularly if there are compatible signs of infection or indwelling devices.

The absence or resistance gene detection suggests susceptibility to standard regimens, though treatment decisions should be guided by clinical context, local antibiograms, and any corresponding culture data to confirm pathogenic relevance.

Blood Case 1.

Blood Case 2:

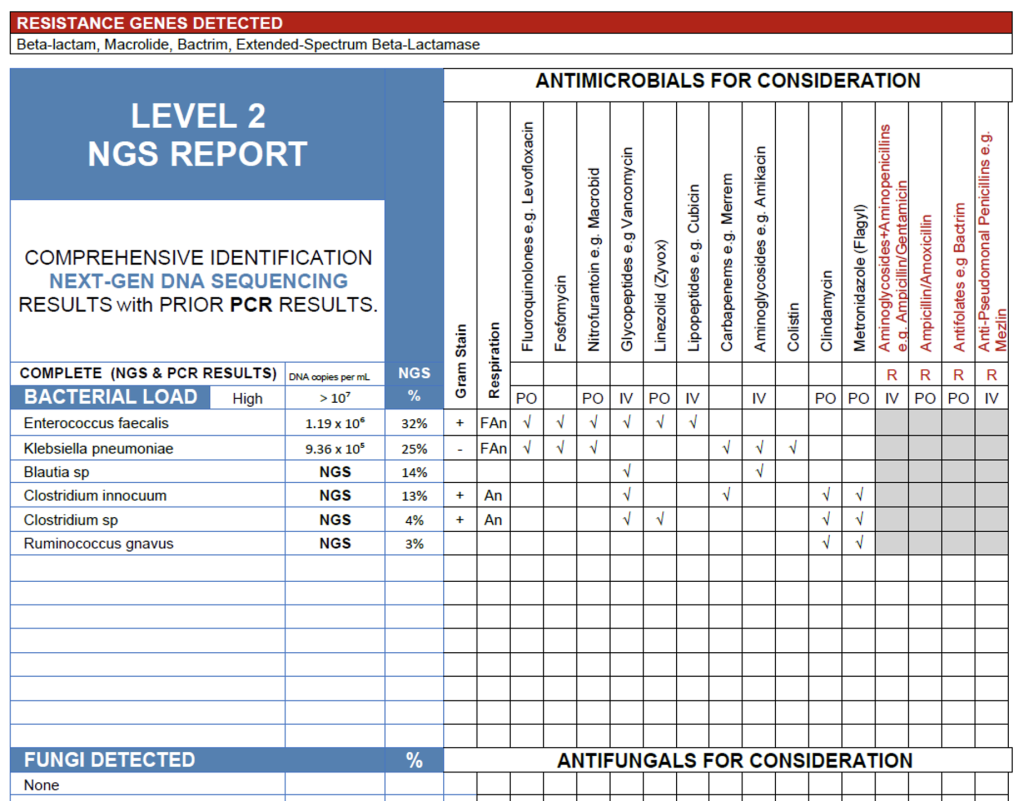

The NGS results from this blood sample show a high bacterial load (>107 copies/mL) dominated by Enterococcus faecalis (32%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (25%), both of which are well-recognized bloodstream pathogens and likely contributors to active infection in a symptomatic patient. The presence of β-lactamase, macrolide, Bactrim, and ESBL resistance genes suggests that one or both organisms harbor clinically significant resistance mechanisms, warranting antimicrobial selection guided by susceptibility data or molecular resistance findings. Secondary anaerobic detections including Blautia sp., Clostridium innocuum, Clostridium sp., and Ruminococcus gnavus are common intestinal commensals and may represent low-abundance or non-viable DNA translocated from the gut rather than true pathogens. Overall, the profile is consistent with a polymicrobial bloodstream infection of gastrointestinal or genitourinary origin driven primarily by E. faecalis and K. pneumoniae.

Blood Case 2.

When interpreting blood NGS reports, it is important to integrate organism profile, relative abundance, and resistance gene findings with the patient’s clinical presentation. As illustrated by the two examples, one showing a low bacterial load without detected resistance genes and another with a high load and multiple resistance markers, the clinical significance of each organism depends on its pathogenic potential, abundance, and context. The Antimicrobials for Consideration table included on each report is intended to as a quick-reference tool, summarizing typical wild-type sensitivity based on established resources such as the Johns Hopkins and Sanford Guides. It should not be interpreted as an antimicrobial susceptibility test result, nor is it exhaustive. Not all possible therapeutic compounds are listed, and the final selection of antimicrobial therapy remains at the discretion of the treating clinician, who may choose an alternative or additional agent based on patient-specific factors, institutional formulary, or clinical judgement.

Next, we will turn our attention to the brain and central nervous system.

Brain Abscess Case:

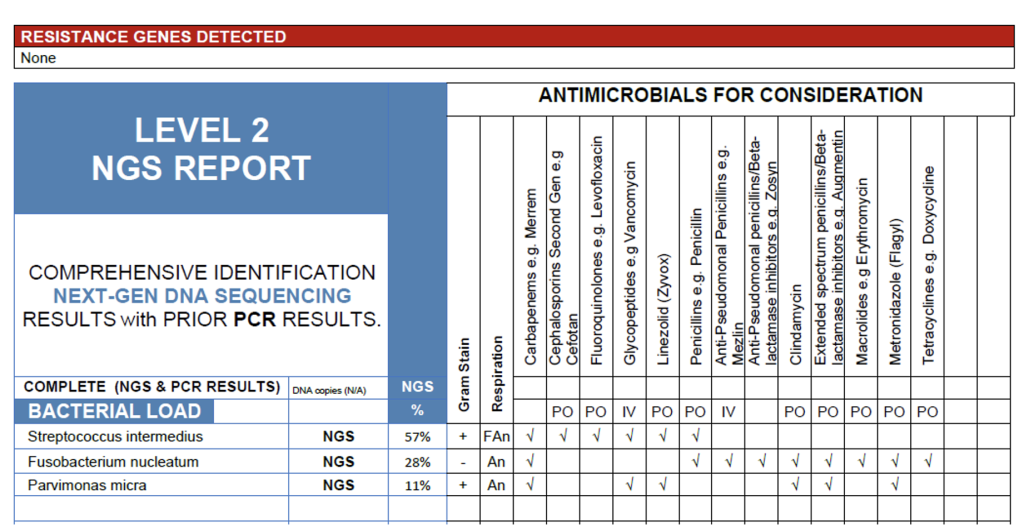

The NGS findings from this brain abscess sample reveal a polymicrobial infection dominated by Streptococcus intermedius (57%), accompanied by Fusobacterium nucleatum (28%), and Parvimonas micra (11%). This combination is characteristic of abscesses originating from oral, sinus, and hematogenous sources, where facultative and obligate anaerobes act synergistically to promote abscess formation. S. intermedius, a member of the Streptococcus anginosus group, is well known for its abscess-forming potential and likely represents the primary pathogen. The co-detection of F. nucleatum and P. micra further supports an anaerobic infectious process rather than contamination, as all three organisms are commonly implicated in deep-seated cranial infections. No resistance genes were detected, suggesting susceptibility to standard empirical regimens for mixed aerobic-anaerobic infections, to be refined based on clinical course and antimicrobial response. It is important to note that testing for antimicrobial resistance genes is not a comprehensive test for all resistance mechanisms and negative results do not rule out other resistance mechanisms.

Brain Abscess Case.

CSF Case:

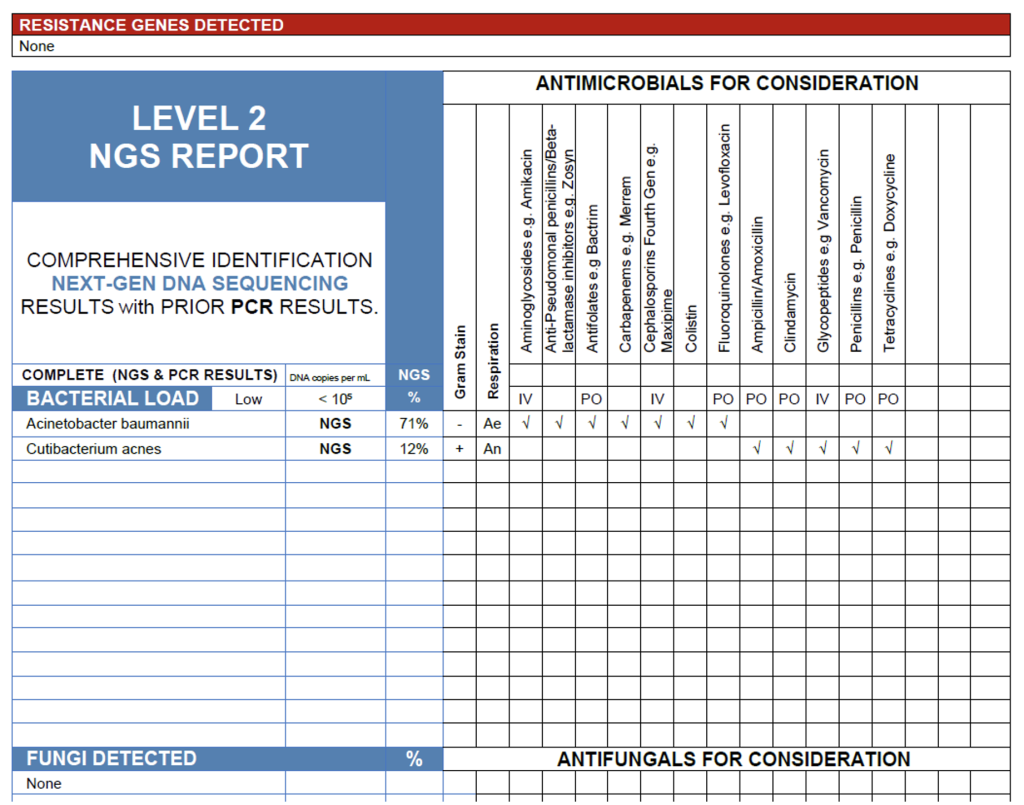

The NGS results from this cerebrospinal fluid sample reveal a low overall bacterial load (<105 copies/mL) with Acinetobacter baumannii (71%) as the dominant organism and Cutibacterium acnes (12%) present at lower abundance. In a symptomatic patient, particularly one with neurosurgical hardware, recent head trauma, or ICU exposure, the detection of A. baumannii is clinically significant and may represent an early or partially treated infection, as this organism is a recognized cause of healthcare-associated meningitis and ventriculitis. Conversely, C. acnes is a common skin commensal and frequent contaminant in CSF specimens; its low-level detection is more consistent with background DNA or minor contamination during collection. Overall, the results support A. baumannii as the likely pathogen, with C. acnes unlikely to be contributing to active disease.

CSF Case.

Interpretation of NGS results from cerebrospinal fluid or other samples from the central nervous system requires careful distinction between true central nervous system pathogens and background DNA introduced during sampling or from skin commensals. As demonstrated in the two examples, higher-abundance detections of organisms such as Streptococcus intermedius or Acinetobacter baumannii, both known causes of intracranial abscess and meningitis, should be considered clinically significant when correlated with compatible symptoms, imaging, or laboratory findings. In contrast, low-level detections of common skin flora such as C. acnes are often incidental and should be interpreted cautiously unless supported by evidence of hardware-associated infection or chronic inflammation. NGS provides valuable diagnostic insight in CNS infections by revealing fastidious or partially treated pathogens may escape culture detection, but results must always be integrated with clinical presentation, CSF parameters, and imaging to ensure accurate interpretation and avoid over-calling contaminants as causative agents.

Now we will bring our attention to ENT specimens.

MARCONs in Sinuses:

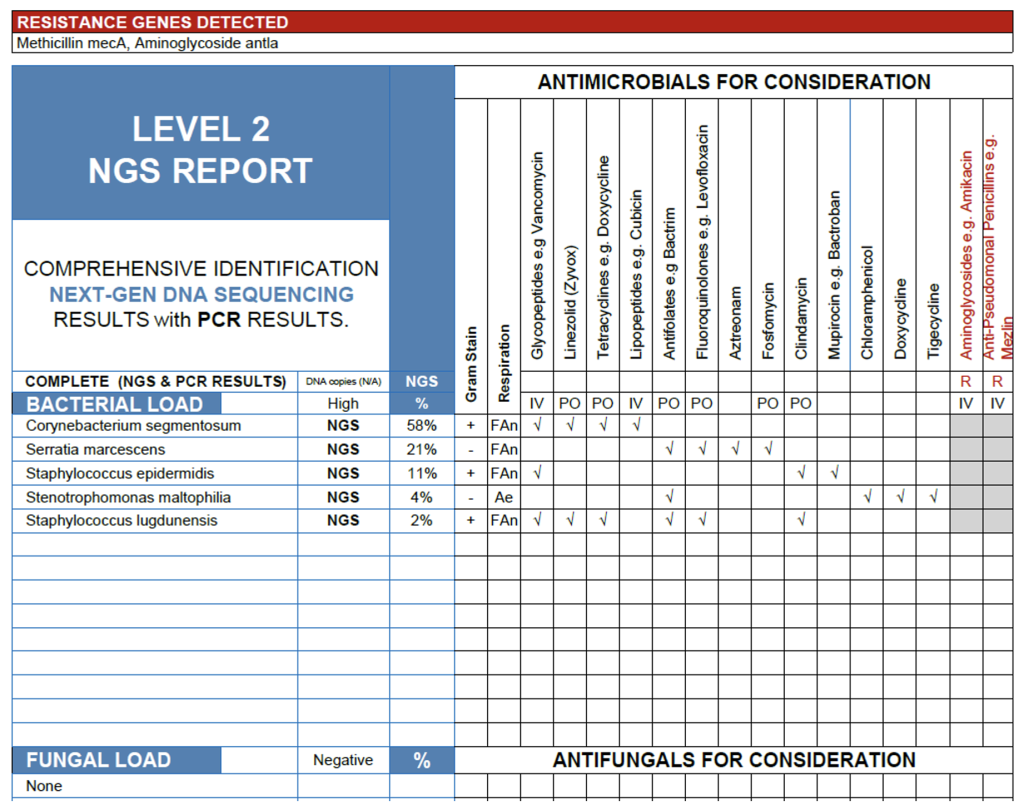

The NGS profile from this sinus specimen reveals a high overall bacterial load with a mixed aerobic and facultative anaerobic community dominated by Corynebacterium sementosum (58%) and Serratia marcescens (21%), alongside Staphylococcus epidermidis (11%), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (4%), and Staphylococcus lugdunensis (2%).

In a symptomatic patient, C. segmentosum and S. marcescens are the most likely contributors to infection, both recognized opportunists in chronic sinus and biofilm-associated disease, particularly after repeated antibiotic exposure or mucosal injury. The detection of S. epidermidis and S. lugdunensis reflects a MARCONS (Multiple Antibiotic-Resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci) pattern often encountered in chronic sinus cultures; NGS adds value here by identifying species-level details and confirming resistance determinants (mecA and aminoglycoside resistance).

Of note, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, though present at modest relative abundance, is a clinically significant pathogen due to its intrinsic multidrug resistance and association with persistent, antibiotic-refractory sinus infections. Its presence warrants careful clinical correlation, particularly in patients with chronic sinus disease, prior antibiotic courses, or indwelling sinus instrumentation.

Overall, C. segmentosum, S. marcescens, and S. maltophilia represent the most plausible infectious contributors, while NGS provides added diagnostic clarity by differentiating coagulase-negative staphylococci and contextualizing antimicrobial resistance markers.

MARCONS in sinuses.

Tonsil Swab:

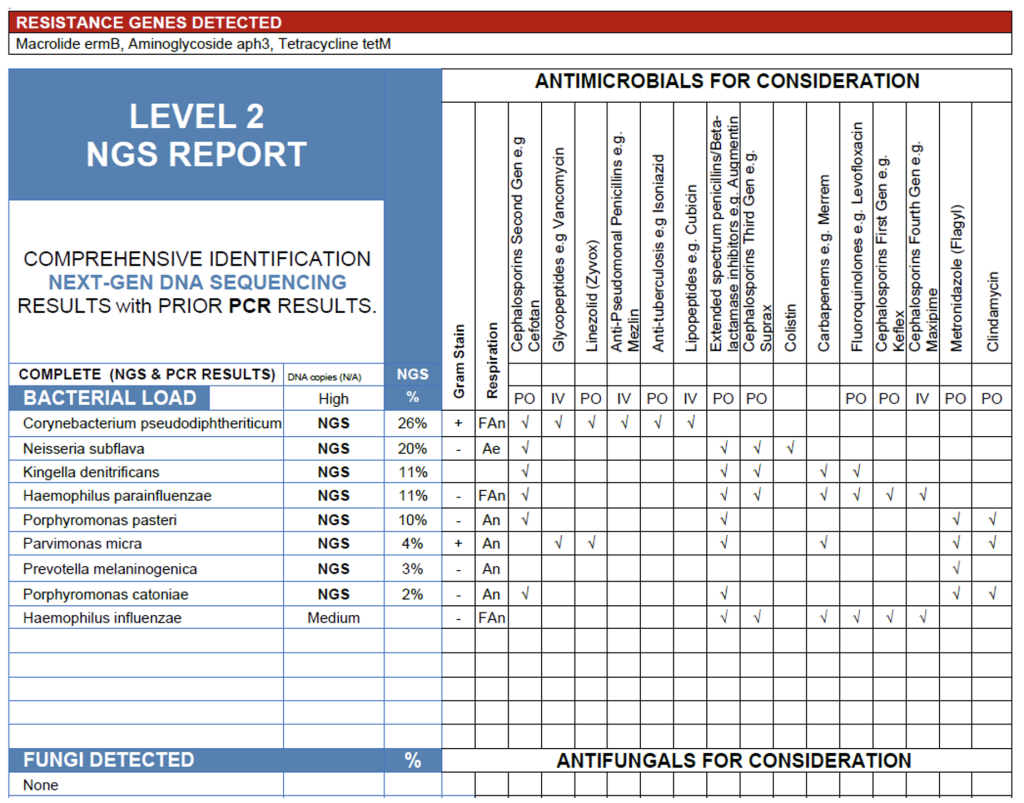

The NGS analysis of this tonsillar swab identified only organisms that are characteristic commensals of the oropharyngeal and tonsillar microbiome, with no detection of established bacterial pathogens such as Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, or Fusobacterium necrophorum. Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum, Neisseria subflava, Kingella denitrificans, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Porphyromonas spp. Parvimonas micra, and Prevotella melaninogenica are all typical non-pathogenic residents in healthy individuals and are not associated with acute tonsillitis or pharyngitis in immunocompetent hosts.

It is worth noting that Haemophilus influenzae was detected by PCR but fell below the 2% NGS reporting threshold, a reminder that PCR often has a much lower limit of detection than sequencing. As MicroGenDX NGS detects bacteria and fungi but not viruses, these results do not exclude viral etiology, which is statistically the most common cause of sore throat symptoms.

Taken together, the absence of classical bacterial pathogens and the predominance of commensal flora support a non-bacterial source of symptoms. A viral respiratory infection should be strongly considered, and antimicrobial therapy is not indicated based on these results in the absence of clinical evidence for a deep or complicated infection.

Tonsil Swab.

Together, these cases underscore the interpretive value of molecular diagnostics in upper-airway infections. In chronic sinus disease, NGS can uncover complex, multidrug-resistant biofilm communities that traditional culture often underrepresents. Conversely, in tonsillar specimens dominated by commensal flora and lacking recognized pathogens, the same technology can support a viral or inflammatory etiology. The distinction emphasizes that sequencing results must always be integrated with clinical findings; symptoms, anatomic site, and patient history to determine when the detected organisms are causative agents versus normal residents of the airway microbiome. Ultimately, precision in ENT diagnostics relies as much on clinical context as on molecular resolution.

Let’s head over to Pulmonology.

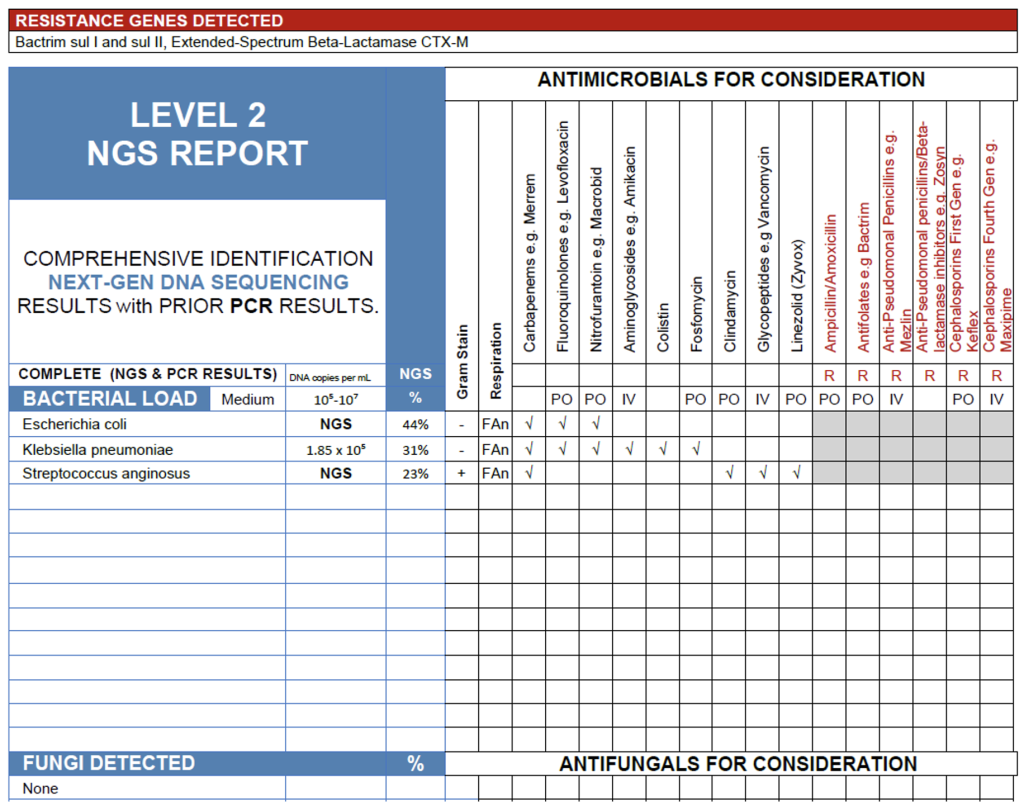

Lung Lobe Tissue in FFPE:

The NGS results from this FFPE left lung lobe specimen show a medium bacterial load (105-107 copies/mL) with Escherichia coli(44%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (31%), and Streptococcus anginosus (23%) comprising a cohesive polymicrobial profile consistent with lower respiratory tract infection. All three organisms are recognized pulmonary pathogens, often associated with aspiration pneumonia, abscess formation, or secondary infection of compromised lung tissue. The detection of sulI/sulII and CTX-M resistance genes indicates the presence of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and extended-spectrum β-lactam resistance among the Gram-negative organisms, further supporting their clinical relevance. Given that this specimen is formalin-fixed tissue with minimal contamination risk, these findings are most consistent with a true mixed bacterial infection rather than background or non-viable DNA.

Lung lobe tissue in FFPE.

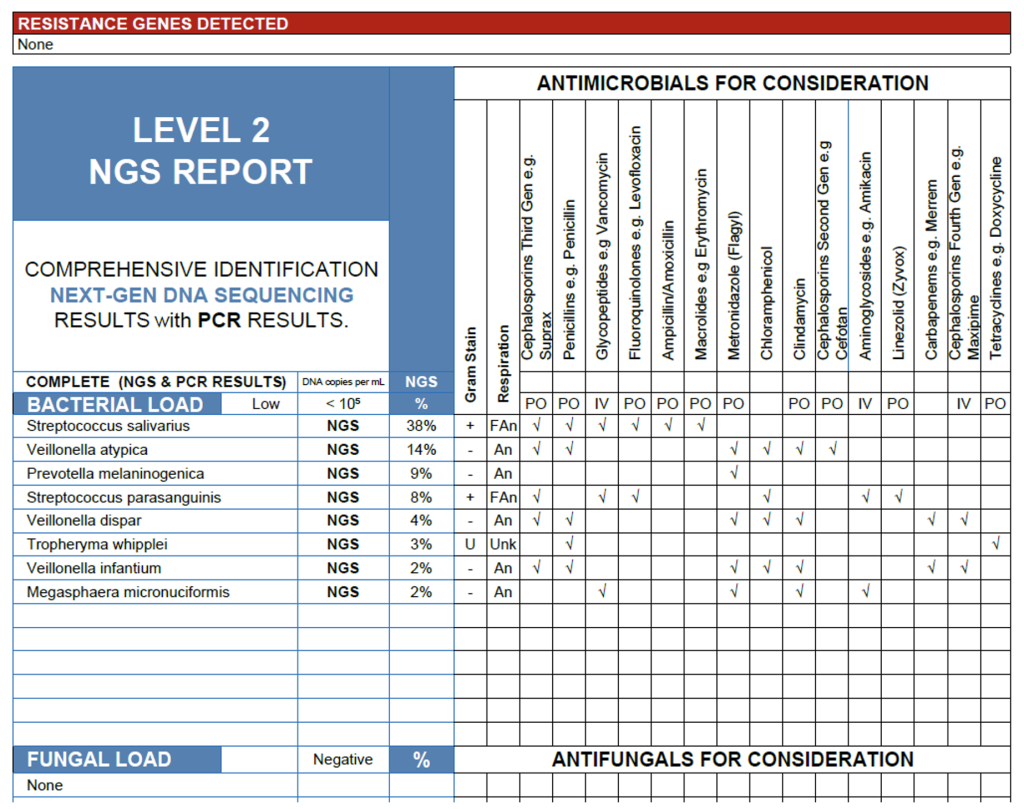

BAL Sample:

The NGS results from this BAL sample reveal a low overall bacterial load with a community dominated by oral flora, including Streptococcus salivarius (38%), and multiple Veillonella species, consistent with expected upper airway microbiota introduced during bronchoscopy. Prevotella melaninogenica and Streptococcus parasanguinis are common anaerobic and facultative oral organisms that may contribute to inflammation in cases of microaspiration or early aspiration pneumonia, though their modest abundances suggest secondary roles. Of particular note, Tropheryma whipplei was detected at 3%, a clinically significant finding given its established association with systemic Whipple’s disease and reported cases of pulmonary involvement. While the overall microbial burden suggests colonization or contamination, the presence of T. whipplei warrants clinical correlation, particularly if the patient exhibits chronic cough, weight loss, arthralgia, or other systemic symptoms suggestive of disseminated infection.

Interpretation of NGS results from lower respiratory specimens such as BAL and lung tissue requires balancing microbial context, load, and clinical presentation to distinguish true infection from colonization or upper airway carryover. As demonstrated in these examples, a high or moderate bacterial load with known pathogens like E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Streptococcus anginosus in lung tissue is strongly indicative of active infection, particularly when supported by radiologic or histopathologic findings. In contrast, BAL samples with low bacterial load and predominance of oral commensals often represent contamination during bronchoscopy or transient colonization, though detections of uncommon but significant organisms such as Tropheryma whipplei warrant careful clinical follow up. Unlike culture, which may miss fastidious or metabolically inactive organisms, NGS provides a comprehensive view of the pulmonary microbial milieu capturing both dominant pathogens and subtle signals that may inform diagnosis, guide antimicrobial selection, and refine understanding of lower respiratory disease pathogenesis.

Need a bathroom break yet? No? Let’s get into urogenital samples.

The Vaginal Swab:

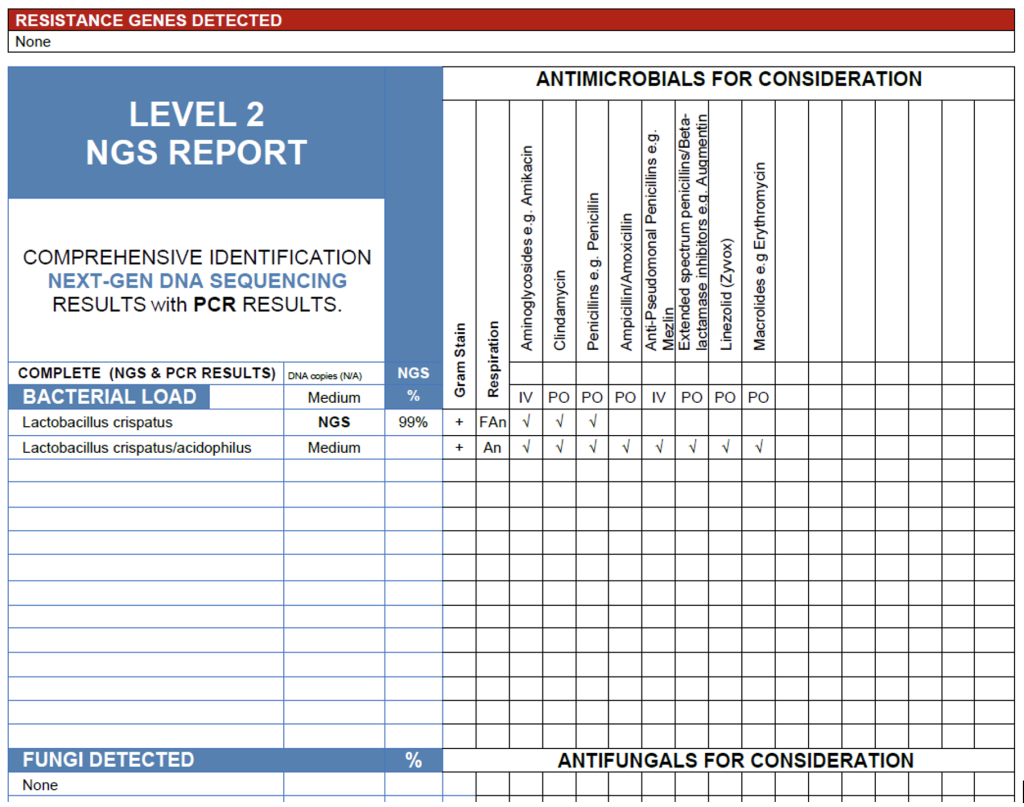

The NGS results from this vaginal swab reveal a medium bacterial load composed almost entirely of Lactobacillus crispatus(99%). Rather than representing a microbiologic “false positive,” this finding accurately reflects the molecular signature of the specimen and, given the absence of skin flora or GI flora, implies a good collection technique and minimal contamination. L. crispatus dominance is a hallmark of a healthy, protective vaginal microbiome. This species maintains a low pH and produces hydrogen peroxide, limiting the growth of anaerobes and pathogens. In this context, the result has a very high positive predictive value for normal vaginal flora and therefore a very high negative predictive value for disease, unless the clinician has an unusually high pretest probability that Lactobacillus itself is causing symptoms, which would make little clinical sense. As a result, NGS provides exactly the information the ordering clinician needs: the patient’s symptoms are unlikely to be explained by vaginal dysbiosis, and further diagnostic investigation should be directed toward alternative anatomic sources, such as the urinary tract.

The Vaginal Swab.

The Urine:

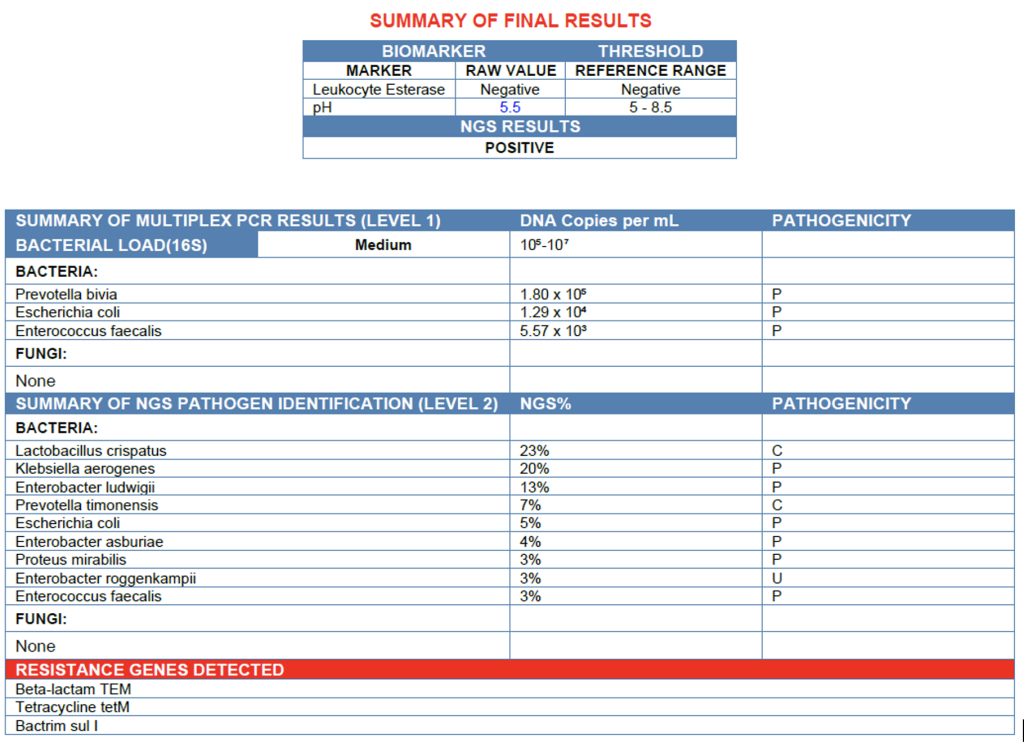

The findings from this urine sample reveal a medium bacterial load consistent with infection, characterized by a polymicrobial community dominated by Klebsiella aerogenes, Enterobacter ludwigii, and Escherichia coli, all recognized uropathogens. The presence of multiple Enterobacteriaceae species, along with β-lactam (TEM), tetracycline (tetM), and sulfonamide (sulI) resistance genes, suggests a biofilm-associated infection, where organisms form a structured community that promotes antimicrobial tolerance and persistent infection. This likely explains the negative leukocyte esterase biomarker, as biofilm-embedded bacteria often evade host immune detection, producing minimal inflammatory response despite ongoing infection.8 Secondary organisms such as Enterococcus faecalis and Proteus mirabilis may further stabilize the biofilm matrix, contributing to chronicity. Meanwhile, Lactobacillus crispatus and Prevotella species reflect background vaginal or periurethral flora introduced during sample collection. Overall, the results are most consistent with a low-inflammatory, biofilm-associated urinary tract infection driven by multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.

The Urine.

When interpreted together, the vaginal and urine NGS results provide a cohesive view of the patient’s clinical presentation. The vaginal swab demonstrated a healthy, Lactobacillus cispatus-dominant microbiome, ruling out vaginitis or imbalance as a source of symptoms. In contrast, the urine sample revealed a polymicrobial population of Klebsiella aerogenes, Enterobacter ludwigii, and Escherichia coli harboring several resistance genes, findings consistent with a biofilm-associated urinary tract infection. The discordance between a normal vaginal profile and a resistant, low-inflammatory urinary biofilm strongly supports the bladder or lower urinary tract as the origin of symptoms rather than the vagina. This case illustrates the diagnostic clarity provided by paired-site NGS testing when traditional markers such as leukocyte esterase are negative and cultures may fail, sequencing can still reveal clinically significant infections that persist by evading both immune recognition and standard diagnostic methods.

Conclusion: The Rules of Thumb for Navigating the Genomic Galaxy

If you’ve made it this far without losing your towel or your temper, congratulations! You should be marginally less terrified of next-generation sequencing than when we started. As you’ve seen, interpreting NGS isn’t rocket science; it’s simply a matter of context, abundance, and biology conspiring in occasionally inconvenient ways.

Before we get to the rules of thumb, it’s worth stepping back to remember how clinicians actually use diagnostic tests in the real world. A good clinician begins with pretest probability, not a sensitivity table. NGS then provides an exceptionally sensitive snapshot of what is truly in the specimen, far more complete than culture, and it’s the clinician’s job to interpret that picture through the lens of positive and negative predictive value. Modern medicine tends to focus on sensitivity and specificity, but those metrics don’t tell you what a result means for the patient in front of you. Predictive value does. When you combine the molecular accuracy of NGS with a working knowledge of the normal microbiome and the clinical presentation, you get a far more grounded interpretation than any culture report could ever offer.

So here are a few rules of thumb to help you on your NGS journeys:

- Context is everything. The same organism that’s a villain in blood can be bystander in the bladder or a hero in the vagina. Always interpret microbial findings in the company of the patient, not in isolation.

- Abundance tells a story. High copy number and dominance are the microbial equivalent of shouting; trace detections are more like whispering in the background – possibly important, but often just the hum of the universe.

- Resistance genes change the plot. Their presence adds complexity, sometimes turning a routine infection into an epic saga of therapeutic improvisation.

- Biofilm changes the rules. They can drive persistent, low-inflammatory infections that evade both host defenses and culture-based detection. When symptoms persist but leukocyte esterase, nitrites, CRP, or other common biomarkers and the cultures stay quiet, think biofilm.

- A “false positive” isn’t always false. Sometimes it’s a clue pointing to equilibrium rather than disease, a friendly signal that all is well in the microbial cosmos.

And finally, remember: NGS doesn’t replace clinical judgement – it illuminates it. It’s the subspace communicator of modern diagnostics, capable of revealing what culture can’t, but still relying on a human at the helm to make sense of the message.

So take a breath, trust your instincts, and keep your towel handy – the microbial universe is vast, but now, at least you’ve got a map.

So long, and thanks for all the fish.

References:

- Contreras ES, Deiparine S, Ulrich MN, Alvarez PM, Bishop JY, Cvetanovich GL. The utility and cost of atypical cultures in revision shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021 Oct;30(10):2325-2330. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.02.016. Epub 2021 Mar 9. PMID: 33711497.

- Pham VH, Kim J. Cultivation of unculturable soil bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 2012 Sep;30(9):475-84. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.05.007. Epub 2012 Jul 7. PMID: 22770837.

- Solden, Lindsey M. et al. “The bright side of microbial dark matter: lessons learned from the uncultivated majority.” Current opinion in microbiology31 (2016): 217-226 .

- Wade W. Unculturable bacteria–the uncharacterized organisms that cause oral infections. J R Soc Med. 2002 Feb;95(2):81-3. doi: 10.1177/014107680209500207. PMID: 11823550; PMCID: PMC1279316.

- Miao Q, Ma Y, Wang Q, Pan J, Zhang Y, Jin W, Yao Y, Su Y, Huang Y, Wang M, Li B, Li H, Zhou C, Li C, Ye M, Xu X, Li Y, Hu B. Microbiological Diagnostic Performance of Metagenomic Next-generation Sequencing When Applied to Clinical Practice. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Nov 13;67(suppl_2): S231-S240. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy693. PMID: 30423048.

- Su, S., Wang, R., Zhou, R., Bai, J., Chen, Z. & Zhou, F. (2024) Higher diagnostic value of next-generation sequencing versus culture in periprosthetic joint infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 32, 2277–2289. https://doi.org/10.1002/ksa.12227

- Hantouly, A.T., Alzobi, O., Toubasi, A.A., Zikria, B., Al Dosari, M.A.A. and Ahmed, G. (2023), Higher sensitivity and accuracy of synovial next-generation sequencing in comparison to culture in diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 31: 3672-3683 1795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-022-07196-9

- Yamada KJ, Kielian T. Biofilm-Leukocyte Cross-Talk: Impact on Immune Polarization and Immunometabolism. J Innate Immun. 2019;11(3):280-288. doi: 10.1159/000492680. Epub 2018 Oct 22. PMID: 30347401; PMCID: PMC6476693.

Authored by Nicholas Sanford, PhD, BCMAS

Medically Reviewed by Dr. Clifford Martin, MD, MBA, DTM&H

[1] In this study, the cost of aerobic, anaerobic, fungal, and AFB cultures were $228.00, $72.00, $47.00, and $613.00 respectively. The total cost of the complete culture set was $960.00 per sample. In periprosthetic joint infections, it is standard practice to collect 5-6 samples from a suspected joint.